● Berlin

Lucas Reiner

Czernowitz and Los Angeles Trees

18.5. – 30.6. 2024

Opening

Saturday, May 18, 2024, 4–7 p.m.

Works

LUCAS REINER: BAÜME UND STADT

By Peter Frank

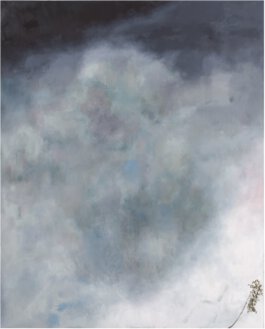

On the face of the earth, there are or at least seem to be more trees than people. And the trees are much more various, and much more peaceful, and braver. They defy our expectations even as they embody them: what are these supposed masters of the forest doing by the side of a coarse city street? How do they survive there? What do they mean, what do they indicate, by being in such unlikely locales, such anomalous sites? What do they mean to nature? To us?

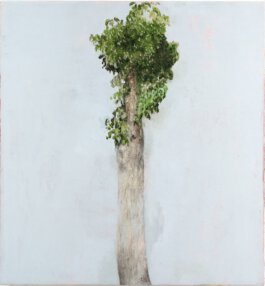

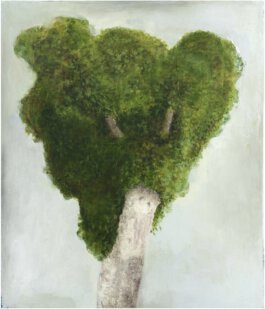

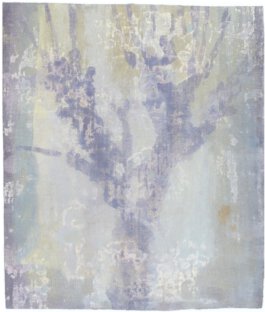

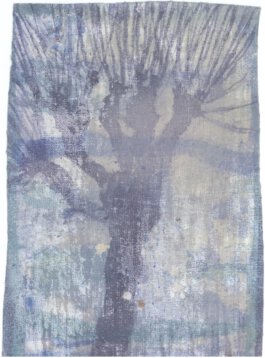

Cities are no place for trees, maybe not even in the magnificent parks we build so we can breathe in the urban environment. But there are cities and there are cities. Lucas Reiner grew up in Los Angeles, on the edge of the desert and the sea and themountains, where it is not uncommon to see a sturdy oak next to a bulbous cactus next to a soaring palm, magnificent and absurd.The Los Angeles Basin is something of a natural hothouse, an urban arboretum. But the extravagant glories of Southern California were not where Reiner found his inspiration. By looking in the neglected corners of L.A. – and in those yet less glamorous plots and pots dotting the world’s cities – Reiner came to know trees as receptacles of emotion, loci of pathos that seem to reflect a wide echo of emotional states, including the infinite small tragedies we all suffer in our own ways. And in paintings such as those comprising his Czernowitz series, Reiner reflects upon the history of such pain – and the pain of such history – by regarding his tortured plants as unforgetting, permanently scarred witnesses.

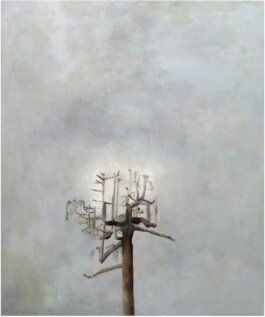

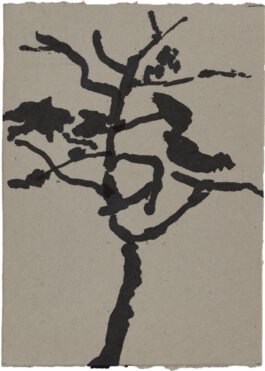

Reiner understands trees either as protagonists in dynamics of woe or as ciphers for such protagonists, immobile marionettes in an endless tale of compromised dignity and dashed hopes. Such a dramatic, even theatrical recasting of these humble growths may seem disproportionate, especially considering Reiner’s stylistic roots in minimalism (evidenced in his recent, provocative “invention” of trees as three-dimensional drawings in space). But this personification of trees, this transfer of narrative potential from human audience to botanic actors, suits not only Reiner’s expressive – expressionist? – intent, but the fervid tenor of the times and technologies we live in and among.An era of sudden and illogical conflict is upon us, and Reiner sees the present malaise manifested in the urban trees he portrays.

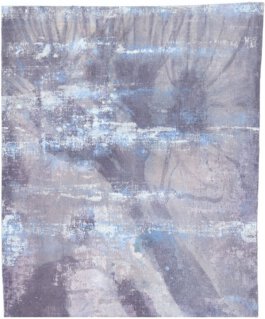

He sees the past in these trees as well. One feels Reiner’s trees bowed not only by the grit and neglect of the city space, but by the restless shadows of the city’s memory. The myriad tragedies, large and small, that transpire where humans live in close proximity, Reiner strongly implies, become impressed upon and absorbed into the nearby vegetation. Not only do these sad but hearty plants witness the march of history, they silently inhere its turbulence and profess its endurance in their own. Those tree sculptures, bent and bowed with pain and frustration, echo Reiner’s pictorial trees, turning the image of angst into its personification.

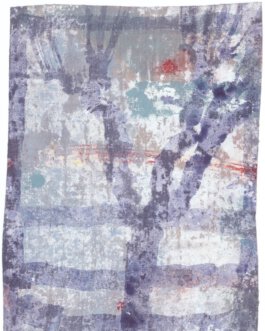

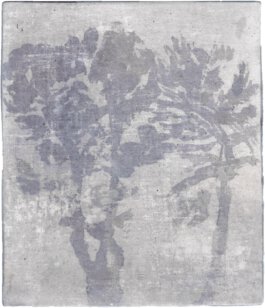

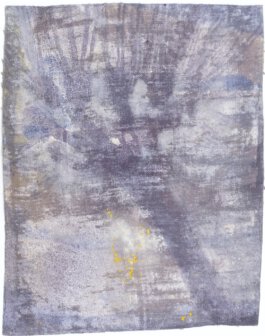

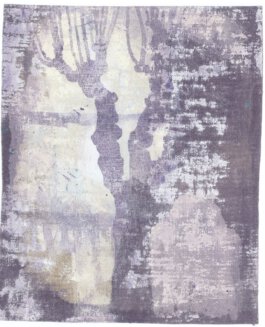

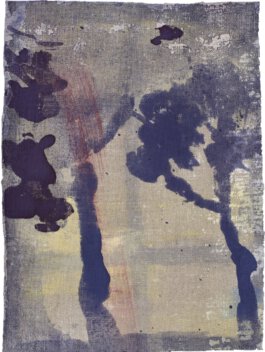

Nowhere in Reiner’s recent work is this more apparent, more chillingly palpable, than in the sequence of 150 seemingly grisaille but in fact purple, brown, and white paintings in tempera, brittle and elusive like century-old photographs, he has rendered under the collective title Czernowitz. On the walls, the paintings attest to the weight of the past, and to the volubility of the present. They cast the trees of the now-Ukrainian town as embodiments of the region’s traumas – most particularly but not exclusively those of the last century.

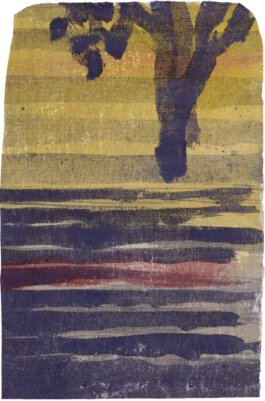

Reiner has also created a book documenting the paintings and the pilgrimage he made to this peculiar destination. It was a voyage, crossing several contemporary (and even more historical) borders from his studio in Berlin, that connected as it could the American painter to his grandfather’s birthplace and milieu. Many immigrant-descended Americans make such trips of ancestor (re-)discovery, but Reiner, framing his task in his artistic means and goals, did not embrace just his grandfather, but a whole way of life, one exclusive to no single religious or ethnic group. The trees Reiner found in Czernowitz – the “pollarded trees” along the regional capital’s boulevards – “reminded me of the radically trimmed street-side trees of my native Los Angeles that I had been painting, drawing, and photographing over the last two decades.”

In the framework of the book, the Czernowitz paintings transform into graphic impressions that frequently and disconcertingly approximate human hands. The images are interspersed not only with Reiner’s own notations, but with fragmentary passages from the writings of Paul Célan, the gray bard of modern European cruelty – and a Czernowitz native. Among the documents are shots of Jewish community buildings and locations, indicating a Jewish population that is vastly reduced but still actively present. In its day, especially under the Habsburgs, Czernowitz was a melting pot, home to at least half a dozen distinct peoples.

There are current and recent efforts to reawaken Czernowitz as a regional cultural magnet, efforts that have reached beyond greater Bukovina and promised a reawakening of eastern European multiculturalism. But the wolf as well as the wizard remain at the door, especially of late. When Lucas Reiner made his way to his grandfather’s birthplace, he was expecting to find a dour backwater in which little of his heritage remained alive. He found a more hopeful place than that, but one that still sits in the path of destruction, depending on which way the path turns. And he found trees imbued with the agonies as well as blessings of the past, ghostly reminders of the sorrows of life and the elusiveness of peace and human harmony. Trees, Reiner reminds us, do not wage war on one another. We wage war on both one another and on them. They prove more durable than we do, to be sure, but they seem to absorb not only our pollutants but our spiritual poisons. As such, they remain silent but insistently, persistently reproachful spirits in our midst, and in Reiner’s art.

Los Angeles

March 2024